“Reprinted with permission from the Omaha World-Herald.”

This article ran Nov. 6, 2005, on the Sunday World-Herald Living section cover.

By Bob Fischbach

World-Herald reporter

He almost didn’t audition, so slim did he think his chances were.

After he did, only one member of the casting team favored him. Most said he was too young.

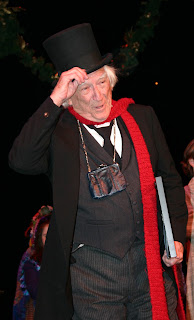

But once cast as Ebenezer Scrooge in “A Christmas Carol” at the Omaha Community Playhouse, Dick Boyd went to work, exploring the role for new insights, plying his craft to get better.

Now in his 30th year as Scrooge, he hasn’t stopped, despite attaining local-icon status. Boyd has played Scrooge to 425,770 people in the city’s longest-running, most popular stage event ever.

It’s hard to imagine anyone else in the role.

But soon, we’ll have to.

Next month, after 818 performances, Dick Boyd will hang up his long red scarf. At 83, he’s no longer too young.

But what a trouper.

“Dick is one of the most consistent men I’ve ever met,” said John Bennett, who compiled and arranged the show’s score. “I’ve never seen him ruffled, and he’s willing to try anything.”

So consistent is Boyd, he’s never missed a performance, a claim no one else can make. Leaving the role is bittersweet.

“I’m looking forward to . . .,” Boyd said. And then a telltale pause.

“Of course, I’d like to go on forever,” he admitted, “but I know there’s a time you should probably step aside. You seem to slide a bit more after 80. It’s always a bit of a worry. They don’t have understudies for this show, you know.”

Charles Jones was in his third of 24 years as playhouse executive director when he wrote “A Christmas Carol,” adapted from the Charles Dickens classic, in the fall of 1976.

Several talented actors showed up at auditions for Scrooge: Bob Roberts, Al DiMauro, Bill Kohl. And an old pro Boyd thought was a shoo-in.

“Bill Bailey was a tough old bird who came off the Orpheum circuit,” Boyd said. “He’d have been my choice.”

Choreographer Joanne Cady recalled five tryout sessions, more than usual. Each man brought something different to the role.

“For Charles, it was very important the role be played as a real, dimensional person and not a caricature,” said Jones’ widow, Eleanor, who was also at auditions. “Realize that a lot of people involved in the casting disagreed with Charles’ choice. But he was adamant.”

Jones later shared why he knew he had found his Scrooge.

“He liked my interpretation of the latter part of it, the joy of redemption,” Boyd said. “He didn’t want to dwell on the gloom. He masterfully alternated scenes, up, then down, but in those final scenes he plays joy to the hilt, leaving the audience feeling really good.”

Never intended as an annual event, “A Christmas Carol” was one of six regular-season shows for 1976-77.

“And one of the roughest productions that ever came along,” recalled Eleanor Jones. The show, laden with special effects, scene changes, a cast of 44 and 18 musical numbers, was a huge undertaking with only the regular six-week production schedule. It wasn’t ready on opening night.

But “A Christmas Carol” was an instant hit. World-Herald reviewer Doug Smith singled out Boyd’s “moving conversion from misanthrope to philanthrope” in labeling the show “a splendid draught of holiday cheer.”

Boyd found that gratifying because he considers that transformation the most challenging aspect of the role.

“Playing the miser’s not hard. Being out of your mind with happiness at the end is not hard. But that quick transition from crying my eyes out to dancing — it’s hard to get that across believably.”

Ticket demand soared through the three-week run that first year. After that, Eleanor Jones said, “each year we had two questions: Could it happen again, and would Dick do it?”

The answer was always yes.

In fact, Boyd insists, there has never been a night he didn’t want to go on. Not when teaching full time. Not when he had the flu. Not when bad knees required joint replacement surgery. Not when howling winter storms made crossing the bridge from his Council Bluffs home hazardous.

When his wife, Miriam, got tired of not seeing him from October until Christmas, she joined the cast. (This is her 17th year.) If Miriam resented the years she put up the Christmas tree alone and ferried four kids to music and dance lessons, she’ll never admit it.

“That’s what he wanted to do, and that was fine with me. He’s been a wonderful husband and father. He gives a lot of himself to others. I think he’s the greatest.”

So do lots of “Christmas Carol” veterans.

“Working with Dick is always a pleasure,” said Marianne Young, who has played Mrs. Cratchit for more than 20 years. “He’s a very nice man, certainly not an arrogant performer, and he treats everyone with respect. And he always thinks there’s something new to find in a scene. Every year he says he’s back to try and get it right.”

“Dick’s such a kind person,” said orchestrator Bennett, “and he has one of the best singing voices in the cast.”

Boyd is quick to credit other cast members: the dignity of the late Mary Peckham as the Ghost of Christmas Past; the sauciness of Julie Huff, who has that role now; the jolly spirit of Bob Snipp as the Ghost of Christmas Present; the sweetness of Spencer Newman, his 18th and final Tiny Tim.

“I’ve gotten more out of this show than they’ve ever gotten out of me, I guarantee,” he said. “Just doing the show is the reward. It’s great to look forward to, every time.”

Critics have occasionally faulted Boyd’s diction, something he says Jones worked hard with him on from day one. Boyd says he’s constantly on guard to maintain the energy level and freshness and yet avoid overplaying.

But it’s hard to argue with hundreds of standing ovations and years of compliments.

“I got a note from a retirement home supervisor who brought a group to the show,” Boyd recalled. “One gent was really the epitome of Scroogelike behavior. But after the show he changed. Actually changed.”

Boyd’s favorite scene?

“I love the one with the kids, chasing them around my office,” Boyd said. “The kids get such a kick out of it, getting the best of me. They never get tired of it.”

Or of Boyd.

“He’s always been excellent with kids,” said choreographer Cady. “At the first cast meeting, he makes sure he goes to each new child, finds out their name, gets to know a tiny bit about them. The past-year kids just run to hug him.”

The first little kid Scrooge threw out of his office, back in 1976, was Charles and Eleanor’s redheaded son, Jonathan.

Late last December, after “A Christmas Carol” had just closed its 29th run, Charles and Eleanor Jones opened their mail together at home. A card with a little redheaded boy stood out. It was from Dick Boyd.

“He said he should have written so much sooner, to express how grateful he was for the opportunity to play Scrooge, how enriched his life had been by it,” Eleanor said.

“When you think of what this man has given, this incredible treasure for the community, and for our lives personally and theatrically — and here he was apologizing. This is the man. Well, we both just sat there and sobbed.”

A few days later, Dick Boyd delivered the eulogy at Charles Jones’ funeral.

“A Christmas Carol” will outlive the participation of all its creators. While playhouse Artistic Director Carl Beck declined to speculate on who will next play Scrooge, he said the show will continue in 2006.

Cast members also refused to speculate, although two actors have played Scrooge for years in the playhouse’s two national touring companies: Matt Kamprath and Cork Ramer.

Whoever is cast, Boyd’s nightcap will be hard to fill.

“He’s one of the most thorough actors in being prepared and grounded,” said Eleanor Jones. “He never goes onstage that it’s not fresh and real and new for him. He keeps it from being any kind of stock character.”

Boyd’s own advice to his successor:

“Just love it, that’s all. Don’t act it. Be it.”

Through the years

“A Christmas Carol” is a technically complex show. Over 29 years and nearly 800 performances, a few snags have become backstage lore.

Snow job: A wintry street scene became something between a blizzard and an avalanche when an overhead snowflake container split, dumping its entire contents on the singers below.

That’s sick: The show must go on, but one year Tiny Tim wasn’t faking illness. He threw up on Scrooge onstage.

Flying bed: Director Charles Jones ordered the top of Scrooge’s four-poster loaded with greens and cornucopia, but somebody forgot to glue it all down. When the bed spun, items flew all over the stage.

Curtain call: After Scrooge dies, an old woman steals his velvet bed curtains. But the first time Mary Peckham tried it, the curtains were firmly stapled into place. Mary had to yank with all her might, and the crowd heard a rrrrrip! Velcro soon solved that problem.

Tough entrance: A door repair made after dress rehearsal required laying the flat on the floor and nailing the door shut. Repair complete, flat back in place. But somebody forgot to remove the nail. Suddenly, in midshow, nobody could enter or exit the Bakery Shop.

Fly away: After Scrooge’s flight from the stage floor to atop the four-poster, the Ghost of Christmas Present must detach the thin cable attached to Scrooge. One night it stuck. Rather than strand Scrooge in midair as the bed left the stage, the ghost called for the curtain to close so the cable could be unhooked.

Another kind of fly: Once, and only once, Scrooge’s quick change from nightshirt to suit for his joyful last scene missed a zipper. The crowd roared as part of the white nightshirt made the oversight obvious to all but Scrooge.

Stand-in: When the Ghost of Christmas Present got laryngitis, director Carl Beck once had to stand in. He’s afraid of heights. “I still have the bruises” from Beck’s tight grip on his arm atop the four-poster, Dick Boyd joked.

Dick Boyd

Born: May 1922 in Nebraska City.

Married: Miriam Hieronymus Boyd, daughter of the former president of Midland College in Fremont, Neb., in 1950.

Children: Richard, Carol, Lynne and Ann. Eleven grandchildren. One great-grandchild.

Education: Bachelor’s degree from Midland College; master’s in education from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

Military: Army Air Corps, World War II veteran of the South Pacific.

Profession: Taught four years in Shelby, Neb., one year in Ceresco, Neb.; auto supply store manager in Council Bluffs, seven years; middle-school language arts teacher in Council Bluffs, 28 years. Twice president of Council Bluffs Education Association. Outstanding teacher award, 1988.

Notifications