Some call it The House That Charles Built. With good reason.

When Charles Jones was hired to lead the Omaha Community Playhouse in Summer 1974, the theatre had a proud 49-year history. But it was struggling, financially and creatively.

Charles Jones

When Jones left 23 years later, he had transformed the Playhouse into a crown jewel of Omaha arts venues with a national, and even international, profile.

Of dozens who have left a lasting legacy in OCP’s first century, the visionary gentleman from Georgia tops the list.

Under Jones, the Playhouse doubled its building size, making possible year-round shows on two stages — plus space for rehearsals and classes. He more than quadrupled its full-time staff, boosting production values. Big, glitzy Broadway musicals became audience favorites at OCP. A fundraising wiz, Jones quickly built support from Omaha’s business and philanthropic elite while directing the annual Aksarben Coronation.

His secret weapon was effusive Southern charm that made each donor, staffer, actor or volunteer feel essential — and that his dreams were theirs too.

With a professional touring arm Jones founded in 1976 — the Nebraska Theatre Caravan — the Playhouse reputation for excellence spread far and wide. Partnering with the Nebraska Arts Council and the National Endowment for the Arts, the Caravan took an annual season of four shows and in-school workshops to more than 160 Midwestern cities and towns.

An adaptation of Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol, which Jones penned in 1976 and meticulously staged, remains a beloved annual classic in Omaha. From 1980 to 2016, the Nebraska Theatre Caravan also toured A Christmas Carol with up to three annual casts, reaching more than 600 cities in 49 states and four Canadian provinces.

Three times OCP took shows to Europe. Once it sent emissaries to Japan.

The professional actors Jones hired for tours became a core talent pool that, in turn, raised the game of local actors.

The exceptional staff he built stuck around, becoming a well-oiled machine greater than the sum of its parts, pushing one another — and Jones — to new heights. Scenic and lighting designer Jim Othuse, choreographer Joanne Cady, music directors John Bennett, Jonathan Cole and Jim Boggess, costumers Denise Ervin and Georgiann Regan set a high bar for audience expectations.

Many professionals Jones hired for the Caravan shaped careers in Omaha. Among them, actor-directors Carl Beck and Susan Baer Collins, actors Jerry Longe and Carolyn Rutherford Mayo (she also managed the Caravan), production coordinator Greg Scheer, technical director Don Hook and sound designer-master electrician John Gibilisco became Playhouse mainstays.

Under Jones’ direction, the Playhouse became the nation’s largest community theatre in physical size, budget size, attendance and season subscribers. In short, Charles Jones was a larger-than-life dynamo — a rare combination of artistic, administrative and social skills that elevated OCP in every way.

His story had an unlikely beginning. Charles Jones was born in Columbus, Ga., in 1938. His grandfather owned Jones Dairy in nearby Smith Station, Ala. Charles loved the farm. Dairy employees were the precocious performer’s captive audience, starting when he was 5. Soon he was writing his own shows.

Chosen for a gifted-student program, he began college at age 15 in LaGrange, Ga. His mother hoped he’d be a minister, but theatre won out. After marrying Eleanor Brodie, he founded the Macon Little Theatre Players, writing original shows with musician Don Tucker.

In 1964 he became artistic director of the run-down Springer Opera House in Columbus. It wasn’t run down for long. Jones headed a massive restoration that led then-Gov. Jimmy Carter to name it the State Theatre of Georgia.

While Charles directed the Springer’s mainstage season, Eleanor ran its children’s theatre. Together they did pioneering work in racial inclusion, finding funds to bus disadvantaged minority children to shows.

In 1972 Charles and Eleanor packed up young sons Jonathan and Geoffrey, moving to London for a year of training at the Polytechnic Theatre Institute.

“He talked his way into that program with two years of correspondence,” Geoffrey said. “One thing Charles does is he wears you down. Somehow he got to London.”

By Spring 1974, Jones was restless to leave the South. He interviewed at theatres in Kalamazoo, Mich., and Omaha.

“Omaha won handily,” Geoffrey said. “Back then the Playhouse board had lots of actors — Christel Kent, Mary Peckham, Joan Hennecke — and they embraced him. He saw a dynamic theatre community, talent that needed leadership.”

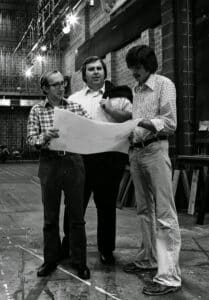

Jones brought Othuse, a stage-design wunderkind he’d hired at the Springer, with him to the Playhouse. For Othuse, Omaha was a leap of faith.

“We worked so well together I kind of knew what he wanted, and he knew how I was going to approach it,” Othuse said. “I’d do anything he asked, because he was the wise one.”

Jim Othuse, Charles Jones and Steve Wheeldon

Othuse wasn’t alone in that thinking.

“Charles was fun to work with,” said Bill Hutson, six-time winner of the Playhouse’s top acting award, the Fonda McGuire. “He made you feel like you were the most important person in the room. He made everybody feel like that. For people who loved doing theatre, it was heaven to be in his rehearsals.”

Also, as openings approached, late-night hell.

A master of crowd scenes, Jones had the staging fully realized in his head. Exactly.

Actor Cork Ramer, who played Scrooge in Caravan tours for 18 years, recalls the rehearsal process well. “Excuse me, darlin’,” Jones would drawl, “but could you move 6 inches to your right? Let’s try that one more time, please.”

That often meant rehearsals ended in the wee hours.

“The late nights were horrible,” said actress Janet Ratekin Williams, another Fonda McGuire Award recipient. “This was community theatre, and we had to get up and go to work in the morning.”

But she loved how he worked with her individually “to make sure we got it right. How lucky we were to have been a part” of Jones’ golden era.

He often added things at the last minute, Ervin remembered. “It might start out simple, but when Charles got his hands on it, it turned out to be a big, big show.”

And if he needed additional resources for that brainstorm?

“He’d pick up the phone, make a speech … and the donor would write the check,” said production manager Scheer. Charles’ opening-night speeches to casts were equally effective, Scheer said.

Geoffrey Jones agreed actors were “sometimes catatonic” by opening night, but they were thrilled with the resulting hit. It kept them coming back.

“He wanted his shows done the way he wanted them,” Geoffrey said, “and he absolutely refused to accept anything less. Compromise was not a word he understood.”

Charles Jones

After a massive stroke in November 1991, Jones’ health went into decline. In a wheelchair for years, he left OCP in 1997 and died in 2005. He was 66.

“A personality bigger than life, that was certainly Charles,” said actor Paul Tranisi, also a Fonda McGuire Award recipient. “He made the Playhouse feel like a professional venue, and he got people onstage to live up to those expectations.”

As his casket left the church, Tranisi recalled, Charles got one last standing ovation.

“The sad thing is, so many now have never heard of the man,” the late Wendy Brintnall, his longtime secretary, said in 2022. “It breaks my heart. My gosh, he’d talk an Eskimo out of ice cubes. He wrote the most beautiful letters to people he needed things from. And it was seldom he didn’t get what he needed. He was such a gentleman.”

Geoffrey Jones said his father would be thrilled to know the show has gone on. “The Playhouse, for Charles, was the love of his life,” Geoffrey said. “It was his building, his show. It was his pride and joy.”

Lasting Legacies with Bob Fischbach

As part of our centennial celebration, OCP will share monthly feature-length articles by OCP board of trustees’ member Bob Fischbach that salute key individuals and patrons who made a lasting difference in the legacy of the Playhouse’s first 100 years.