By Director Suzanne Withem

I read The Seagull and The Cherry Orchardin undergrad and I’d skimmed Uncle Vanya and Three Sisters, but I’d never really connected with the stiff language or strange characters in such foreign situations dealing so poorly with what appeared to be relatively mundane problems. People told me Chekhov was funny, but just reading the text, I didn’t get it. I felt dumb and irritated, so I just gave up on it and joined the “I Hate Chekhov” camp.

Then, in 2006, I auditioned for the Brigit St. Brigit Theatre production of The Seagull and was cast in the role of Nina. My vanity and being cast in a lead role allowed me to put aside my dislike of the playwright and I dug in trying to understand. It helped that the Artistic Director, Cathy Kurz, chose Tom Stoppard’s translation of the play. It was much more accessible than others I’d read, and after having compared different translations of Molière’s Tartuffe, I realized how important a good translation can be. A translator attempting to do a literal translation ends up with a product that sounds awkward and stiff – as if Google Translate did half the work. A literary translation, on the other hand, sticks to the spirit and intention of the original while allowing freedom of interpretation and providing space for the actors to play. That’s what I found in Tom Stoppard’s translation.

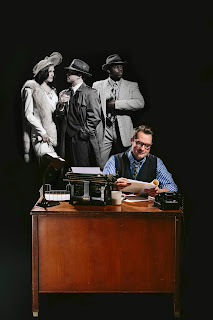

That was one of my first big roles out of college, and I took it very seriously. I applied all my training and watched and listened to the more experienced actors in the group. Doug Blackburn, Charlene Willoughby and Jeremy Earl, just to name a few, were in that production. Each had training and experience far beyond mine, and I did all I could to keep up with them. Nina’s zest for life in the first two acts and her passion in pursuing her dreams in the third really resonated with me, and I found it easy to get caught up in the character, riding the wave past intermission. However, she returns in the fourth act, having had her soul, career, reputation and heart crushed. I struggled every night to relate to that state. Portraying someone so world-weary at such a young age, having lived a relatively sheltered life, was a real challenge for me. But it was a beautiful experience and production all the same.

When I first read Aaron Posners “sort of adaptation” of The Seagull, I immediately fell in love. His love/hate relationship with Chekhov and his plays was immediately apparent and right in line with where I was, more than a decade after my first encounter with The Seagull. Posner doesn’t just riff on the story; he plays with the original text. He quotes Chekhov, mocks him, undermines him and points at him with a flashing neon sign and composes love songs to him. Only someone with a deep love for the story and the history of American attempts to produce the play could get inside the work in this way.

Not only does he modernize the texts and situations, he modernizes the perspectives. Chekhov, through his character of Konstantin demands “new forms” of theatre from 1898, when declamation and oratory were considered high art. Chekhov and Stanislavsky, at the Moscow Art Theatre were attempting to break with tradition by doing innovative things like having the actors speak directly and naturally to one another or doing mundane things like eating, sitting, and blowing their noses on stage. This was revolutionary at the time. In 2017, Aaron Posner screams through his character of Conrad that we again need “new forms” of theatre, then has us break the fourth wall in new and surprising ways, invites us to try out new ways of expressing emotion through music, movement, poetry and improvisation.

Yet, while both Chekhov and Posner challenge their audiences to consider new types of art that encourage new ways of looking at the world, they still provide for fun, humor and the opportunity to experience empathy. These ridiculous characters who move and talk in ways that surprise the audience are still surprisingly relatable and lovable, despite their flaws.